Elected governments really don’t have much power any more because they have ceded most of it to corporations which we believe we control through share ownership but we are hopelessly wrong.

Corporations are some of the few organisations that have true global influence so if we were to have a global democracy we would want them in our power but as you will see they concentrate power. During the past 30 years of economic rationalism (neo-liberal economics) governments across the globe have sold off huge amounts of their power to private corporations, and deregulated markets allowing these corporations to have a lot more power and influence than ever before. In England, Australia, the USA and Canada the provision of human necessities that were formerly owned and run by the state have been sold. Far worse scenarios have played out in South america, South Est asia and Africa where the IMF and World Bank trapped governments in debt and forced them to sell basic resources to global corporations. Water supply, electricity, public transport, telecommunications, banks, airports, even emergency services were outsourced into private hands. Private schools have been encouraged as well as private health care. The argument for this is that private companies improve customer service and are more efficient, and of course there would be more choice and competition and therefore prices should come down. What we got instead was train break downs and cancellations (Connex in Melbourne), a great stink flowing over Adelaide (Effluent treatment in Adelaide), oligopolies with little competition (TRU and Origen energy), price hikes and lack of water supply in Bolivia, lower wages and more job insecurity in south East Asia and generally a concentration of wealth and power in corporate hands. We lost the power to control these organisations and hold them to account the way we could a government run entity.

These companies are mainly publicly listed companies be they Serco, MacQuarie, BHP or EDS, meaning anyone can buy shares in them and have a vote on who’s on the board of directors and therefore it’s like a small democracy, it’s a shareholder democracy.

Shareholder democracy

So you might say if you have enough money you can still democratise corporations and these are actually better democracies as they truly cross borders. Is this true? Australians are the largest share owners in the world with about 35% of people owning some shares in their own name and everyone who ever worked having some interest in shares via their superannuation fund. (Employer superannuation contributions are compulsory in Australia). So we should see a lot of influence coming from a broad range of people over our major corporations, they should be doing what is best for us because we own them! Right? No.

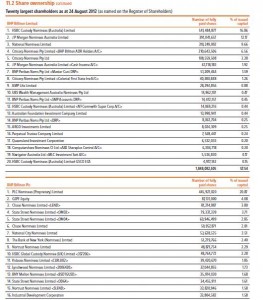

Let’s take two examples; BHP Billiton the biggest mining company in the world which controls more natural resources than any other public organisation, and ANZ Banking Group one of the big 4 banks in Australia. The top 20 share holders of each of these two companies are all nominee or trust (investment) companies with one exception the Australian Foundation Investment Corporation which is a private investment company based in Melbourne. (see table 1 insert table of share holders). And these top 20 shareholders own between 50% and 60% of all the shares. The majority! In ANZ’s case the top 1% of shareholders owns 90% of the shares the other 99% of shareholders 10%. this is where the OWS movement got its “we are the 99% from because it is the same in every major company.

The spin doctors at ANZ and every other major corporation claim to be owned by the people because they have over 100 000’s of shareholders therefore they are democratic. But they are not because the top 20 have all the power, even if all the other shareholders voted in unison it would have no influence at all on the election of the board of directors or resolutions passed. Or dividends paid!

So what are these nominee and trust companies? And can we influence them and therefore the corporations they own? I might add that most public companies have a similar share ownership to ANZ and BHP Billiton the majority of shares are held by a few global nominee and trust companies. A nominee company is a private company; therefore it does not need to produce publicly available annual reports showing their ownership or dealings, they are usually owned wholly by a bank, trading house or investment company. They are essentially a holding company for others, they have ownership rights to the shares and the person/s or companies that use them have beneficial rights to the capital gains and dividends the shares produce. The voting rights are owned by the nominee company but it is “usual” for the nominee company to vote under instruction from the beneficial owner. Each nominee company has its own way in which they do this and some don’t act in this way at all. Some have the beneficial owners register their desire to influence votes, the beneficial owner may not choose to use this power as one of the reasons nominee companies are used is to cut down on the paper work and obligations of share ownership. If they choose to register the nominee company collates these suggestions in private and then votes. It is not mandatory for a nominee company to consult its beneficiaries on how they use their voting rights. Of course a large beneficiary owner may direct the nominee company to use all its votes in a certain manner while hiding their own influence.

Table 1

BHP Billiton http://www.bhpbilliton.com/home/investors/reports/Documents/2012/BHPBillitonAnnualReport2012.pdf

ANZ 2011 Annual report.

http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/IROL/96/96910/2011_Annual_Report_ANZ.pdf

Because of this some corporations actually have limits on the amount of votes a nominee company can exercise. UBS one of the biggest banks in the world (the GFC has had some effect on its current size) limits an individual nominee company to 5% of the total votes. As you can see the desires of the beneficiaries is quite opaque, it’s not absolute that they will have influence over the way the nominee company votes, and if they do it’s not necessary for the nominee company to make public what each beneficiary has instructed.

So why do these nominee companies own so many shares? They essentially own most of the capital in the world and therefore most of the power (votes). There are two main reasons firstly the bank owning the nominee company has lent the beneficiary money to buy the shares in the first place. This is generally called margin lending where a bank will lend 80% of the purchase of price (depending upon the borrower this can be higher or lower) of the shares and the beneficiary puts up the other 20%, and if the share price falls below a point where the loan becomes greater than the value of the shares at current market price they will make a margin call, the borrower has to put more money with the bank to reduce the bank’s exposure to loss. Margin lending is mainly used by traders who are interested in making money through price movements and dividends; they are not interested in controlling the company. As far as I can tell someone in a margin loan through ANZ has no, or at least is not made aware they have voting rights through the shares they are the beneficiary of. This actually makes sense for both parties. Traders turnover a lot of shares and it is hard to track exactly who owns what at the time a resolution needs to be voted on, also traders see the necessity to vote as an added burden, it’s not their core business and are quite happy to pay another company to take care of this for them. The UK has encouraged the use of nominee companies through its stamp duty on share trading. If one uses a nominee company to trade their shares they can reduce or eliminate the stamp duty because the nominee company will make the trades internally therefore not using the public stock exchange and hiding the trade from the tax collectors.

The other major reason is anonymity. You may not want the world to know you have a large stake in a major company. Why wouldn’t you? Well governments may think you have too much influence and are decreasing competition, you may be trying to avoid tax, you may be a board member of a competing company or supplier. You may be incredibly powerful and don’t want the masses to know your influence.

There is also another simply practical reason to use a nominee company, superfund managers often use them because they will take care of the paper work involved with buying and selling large quantities of shares, and the pesky task of voting.

I mentioned earlier that all Australians that have worked have an interest in the shares of companies through their superfund but we don’t get the voting rights, the fund does, and they will often pass this on to a nominee company. The voting rights of nominee companies is at least very opaque, possibly collusive, and most definitely it concentrates power into the hands of a few rather than the many.

Trusts are slightly different to nominee companies, and their purpose varies. Many are family or corporate trusts that are mainly set up for tax purposes to spread income and or franking credits to companies and individuals thus minimising the groups tax burden. Or they are collective trusts such as my employee share trust. The ANZ gives its non-management employees in Australia $1000 dollars worth of shares every year but holds the shares in trust for a minimum of 3 years, and as far as I am aware they hold the voting rights on these shares not us. Again though it concentrates power rather than dissipates it, shareholder democracy is a Furphy.

Governments in the wake of the GFC have called for a cap on the golden parachutes for leaving CEO’s and on short term bonuses for executives particularly in the banking sector, as they see these huge payments as one of the motivations for greedy reckless decision making which lead the world into crisis. Australia’s government has passed responsibility to the shareholders of these companies saying it is they who should take control of their companies and look after their interests by capping CEO remuniration. As you can see this is ridiculous because the shareholders are members of the same club as the board and the CEO. The shareholders are the CEO’s of the past and present. When the largest shareholder of ANZ bank is HSBC nominees it’s the CEO of HSBC and its board which selects the remuneration package for ANZ’s CEO. Note Mike Smith the current CEO of ANZ was ex-HSBC.

The CEO’s then move from the chief executive role to board member and then board manipulator as Don Argus has done moving from CEO of National Australia Bank (nab) in the nineties to chairman of the board of BHP Billiton in the 2000’s and now director of the Australian Foundation Investment Company the biggest independent owner of shares in Australia. It is in their collective best interest to move money away from the community into their own hands. They are the club so they are always going to pay high (relative to what most readers earn) amounts to their CEO’s for doing what they are told.

It’s interesting that one of the few major company’s shareholders that actually gives its CEO flack and can get them to change their policy on corporate decisions is Telstra (formerly Telecom Australia). In 2010 they backed down on charging a fee for non electronic payment of bills because their shareholders complained at the AGM (Annual General Meeting) this is because of the way Telstra was sold. It was a state owned Telco the only Telco in the country when it was privatised and the corporate ownership was limited to 20% and the rest sold to a broad range of “mum and dad” investors including me and my sister. I knew that as soon as the first issue was floated the corporates would want to get their hands on more and therefore push the price up, I sold in the first two months and doubled my money, but most held on and paid all the further instalments. This meant Telstra unlike most other major companies had a broad individual human ownership and that is why they actually must try to become more human themselves.

Telstra’s plummeting share price may be a sign that the corporate club doesn’t like having things out of its control and in the hands of the populous for they seem to put things like fees on them at a higher priority than profits and CEO bonuses.

You will notice in this that the power ratio of a publicly listed company is very similar to the way wealth is divided in the world, 80/20 or 90/10 where 80-90% of the wealth or control is held by 20-10% of the people. That’s not democratic! It’s closer to the one party system of communist China or the feudal hereditary monarchies of the middle ages.

So we can see that we are now ruled by corporations that are controlled by a few that prefer to remain anonymous, and by politicians that are controlled by narrow minded self appointed elite lobbyists, who are most likely to be the same as those that control the corporations.

Just before we leave the fable of corporate democracy I’d like to point out that the two rising superpowers of the world China and India still have most of their basic services like energy, water, telecommunications, and transport in state, or central control. Not in corporate hands. Why do I mention this? Well because they are succeeding, they have money and power on the rise and we have none, perhaps we can take a little bit of that and mix it with a lot of us.

David J Campbell

Author of Fluidity the way to true DemoKratia