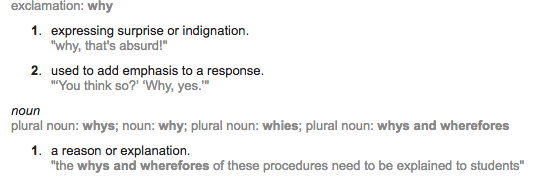

Why am I self aware?

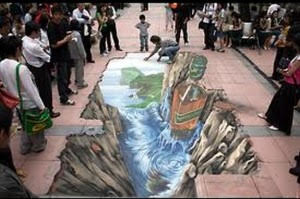

Why am I self aware? I ask why, like a child asking why can’t I fly Daddy. And like Daddy I cannot answer the why question but can describe quickly and easily how a bird flies, how a plane flies, and that a human does not have the apparatus to fly. I can ask why?… Read More Why am I self aware?